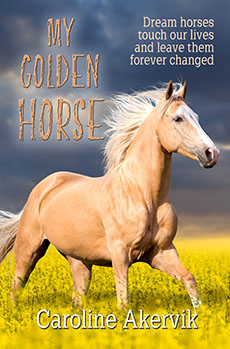

Dream Horses #2

My Golden Horse

by Caroline Akervik

Ellen Sanz is angry at the world, and she wants nothing to do with horses. Before her mother’s accident, they’d had a great life. Her mother, Linda, was a successful show jumper. Ellen had attended virtual school, and they’d travelled between international horse competitions. Everything had changed when Linda suffered a catastrophic riding accident. Ellen has been her mother’s caretaker in the year since. They’ve been forced to move to Linda’s parents’ hobby farm in the Maryland countryside.

Ellen Sanz is angry at the world, and she wants nothing to do with horses. Before her mother’s accident, they’d had a great life. Her mother, Linda, was a successful show jumper. Ellen had attended virtual school, and they’d travelled between international horse competitions. Everything had changed when Linda suffered a catastrophic riding accident. Ellen has been her mother’s caretaker in the year since. They’ve been forced to move to Linda’s parents’ hobby farm in the Maryland countryside.

Here, Ellen finds herself irresistibly drawn to Lemon Meringue, nicknamed Tandy, a show ring sour palomino rescue mare, as well as to Joel, a cute and horse crazy guy.

Can Ellen and Tandy let go of the pain of their pasts to embrace a new life and find that special connection?

Preorder

| ||

GENREHorses |

EBOOKAmazon KindleSmashwords Nook Apple Google Play Kobo |

|

| Middle Grade / Teen | ||

Excerpt

Chapter One

Peering through the trees, Ellen glimpsed the reason she was out in a midafternoon thunderstorm. A palomino horse galloped frantically in the pasture behind her grandparents’ yard.

“Tandy, I’m coming. You’re going to be okay,” Ellen called out to her. What was wrong with Tandy? Why didn’t the mare stay in the shed until the storm ended? There was something ominous and out-of-sorts about this weather. It had been a sunny if muggy June afternoon. Then, the sky had gone dark, and she’d heard the ominous grumble of thunder overhead.

I have no luck, Ellen Sanz reflected. This summer storm was just one more instance in a long line of misfortune that Ellen continued to experience in her sixteen years of life. Besides the horrific accident which had irrevocably altered her and Linda’s, her mother’s, life there had been other incidents which suggested that the fates were aligned against them.

There had been that time when Linda took Ellen snowmobiling up in the mountains around Lake Tahoe. At the time, Ellen had been about seven years old. It was one of the last vacations that she, her mother and her father, Daniel, had taken together as a family. On that day, it had been just the two of them, Ellen and Linda. Linda had said that she “had a special treat planned for them.” Now, nine years later, all Ellen remembered was the sensation of flying along on the snowmobile, an impression of bright blue sky and white snow, then the feeling of being catapulted through the air after her mother took a sharp turn. Ellen had landed so hard she thought she’d broken every bone in her body. She’d been unable to breathe. Predictably, her mother’s first words to her after the accident had been, “Don’t tell your father.”

Ellen hadn’t. Nevertheless, Daniel had left them shortly thereafter. He’d said it wasn’t about Ellen, that he loved her with his whole his heart, but he couldn’t take Linda’s desire to lead a gypsy life as a professional horsewoman. He’d fought hard to have Ellen live with him, but she’d fought equally hard to remain with her mother. Since then, it had been just the two of them, Linda and Ellen, against the world.

Linda had been an elite professional equestrian who lived an itinerant existence. Following clients and their horses, Linda and Ellen had done the winter show circuit in Florida. They’d spent their summers in Annapolis, Maryland, which was within reasonable driving distance of the horse shows in the Northeast. In Maryland, the stables where Linda had ridden had been a little more than an hour away from Linda’s parents, Betsy and Bernard Hogan, so Ellen had spent some time at their hobby farm. Annapolis was also reasonably close to Daniel and his new family, who lived in northern Virginia.

It had been an exciting life travelling from horse show to horse show, but it made attending school difficult for Ellen. She missed large chunks of time. In the end, it had proven easier for Ellen to attend a virtual school. It made sense; she’d argued with Daniel, who’d wanted her to have a more traditional high school experience. She wouldn’t miss anything academic in a virtual as opposed to a traditional school. For a long while, things had worked. Until their luck gave out completely, until THE ACCIDENT.

There was Ellen’s life before the accident and her life after the accident. Before the accident, Ellen and her mother had been a team. Linda competed and Ellen did schoolwork and took pictures of her mother and the beautiful horses she rode and competed. Now, Ellen was living at her grandparents’ hobby farm in Monkton, Maryland, tucked into one of the tiny rooms of their prefab house. It was the summer before her senior year of high school. She felt weird, and out of place. She had no friends in the area.

Standing on the porch, Ellen glared through narrowed brown eyes out at the blackened sky and the wind whipping the tree branches about. “I hate you!” she shouted into the rising wind. That stormy sky summed up her frustration with her life, with all that had gone wrong in the past few months.

Moppy, her cockapoo dog, wriggled in her arms, trying to break free. “No, you’re not getting away again,” she muttered, burying her nose in his soft, dusty curls. “I have to get Tandy. She’s being an idiot like you, running around out in this storm. I’m going to lock both of you up in the barn, where you’ll be safe. This storm’s getting nasty.” The sky exploded with lightning, followed by a resounding boom. Moppy became frantic, scratching Ellen’s short clad thighs with his nails. Flinching, she shifted his almost thirty pounds in her tiring arms. Again, she glanced at the sky, which lit with another bolt of lightning.

“One-one thousand. Two-one thousand.” Boom! The heavens exploded with thunder. Now Ellen kept her head down. It’s terrifying. But I can’t leave Tandy out there in the pasture. She could get hit by lightning. By now, she was half-way across her grandparents’ backyard to the two-stall barn.

The mare’s terrified clarion cry rang out again. “Tandy, I’m coming!” Ellen ran. She was nearly to the middle of the yard, past the garden where plants fluttered frantically in the wind, moving in concert with the branches of the ancient line of oak trees which extended through the yard and out into the pasture. Everything was whipping madly about in the increasingly powerful storm winds.

Thunder boomed again. Ellen heard and viscerally felt the thud of galloping hoofbeats on the summer hardened ground. Tandy. She felt a rain drop hit her smack on the forehead and then another. By now, she was under the first of the gigantic oak trees. Here she was protected from the rain, which was beginning to fall. Nervously, she glanced up at the tree above her. You never want to be under a tree during an electrical storm. That was a rule right up there with never swim alone. But there was no avoiding the row of two-hundred-year-old oaks. The only way out to Tandy and the pasture gate was under the canopy of trees.Glancing back at the house, she saw her grandfather hurrying as best he could with his artificial hip down the back porch steps. He called to her, waving her back to the house, though she could not hear his words over sky booms, hoofbeats, and the terrified horse.

“I have to get Tandy,” she shouted back to her grandfather. “I have to bring her in.”

He shook his head in denial and cupped his mouth, responding to her, but Ellen still couldn’t hear him over the storm sounds. She didn’t want to hear him. I must save Tandy.

Suddenly, she heard another ominous boom and a long, cracking sound. Her heart exploding in her chest, she glanced up to see one of those enormous oak trees plummeting towards her.

* * *

Green. The first thing Ellen was aware of was the color and the smell of green. The world had a dream-like quality, as if she were just waking up. Distantly, she heard voices screaming and calling her name. Green, smooth and cool. Something scratchy on her face. “Ellen! Ell-en!” She shook her head a little, trying to clear out the cobwebs. Her brain wasn’t working right. She knew those voices. It was her Poppa and her Nanna calling her name. They sounded terrified. Ellen felt a tear trickle out of her eye and run down her cheek. Despite everything, she didn’t want things to end here and now with her dead under a tree. I’m sorry I was so horrible, Nanna and Poppa. For so long, all she’d wanted was her old life back. Now she merely wanted to live. She’d figure out the rest later.

“I’m here,” she croaked. “I’m here,” she said again, her voice a little stronger. Then, one of her grandfather’s weathered and scarred hands penetrated the green, leafy world in which she was buried. She reached for the hand, gripped it, and she found herself being drawn through a scratchy, tearing bramble of branches and leaves. Miraculously, she wasn’t pinned under the tree trunk or even a heavy branch. Somehow, the big branches and the trunk of the tree had missed her when they’d fallen to earth after the tree had been struck by lightning.

Now, her grandfather’s arms were around her, hugging her tight. He drew back from her. His tanned and lined face was wet with tears. “We thought we’d lost you.”

Ellen sniffed and swiped at her dripping nose. Understanding of the situation swept through her. “I almost died, right?”

Her grandpa laughed, his kindly face expressing joy and relief.

“Bernie, do you have her?” Her grandmother called from across the yard beyond the wreckage of the enormous fallen tree. Her two Pekinese dogs barked frantically while dashing around her legs. Ellen was relieved to see Moppy dart over to join the rest of the pack. Moppy, I forgot about him, but he’s okay, too. We all made it!

“I have her, Betsy,” Bernie waved to his wife, who clasped her hands to her heart.

A frantic whinny shattered the moment.

“Tandy!” Ellen muttered. “We have to bring her in.”

“You mean, you came out here in a thunderstorm, almost got killed by a tree, all to get that darned horse? There’s a shed on the other side of those stalls. She’s fine. What were you thinking about?”

Ellen didn’t reply right away. She nibbled on her lip and reached up a trembling hand to pull a leafed branch from her hair. The reality of how close she had come to death rattled her. “It’s not just any horse. It’s Tandy. She’s...my friend.”

Bernie rubbed at his face in disbelief. “What is it about this family and horses? We’re all fools. I’ll get the horse. You have a bump on your noggin that’s swelling up. I don’t want you out in this storm.”

“I can get her.”

“No, you can’t. I’ll take care of that darned mare. You get inside and have your mom or Betsy look at that bump and decide whether we should take you to the hospital.”

Still dazed, Ellen nodded and headed to the house. Betsy met her halfway and took her by the arm. Despite how her head pounded with every move, Ellen turned back to the pasture and saw that Bernie had caught Tandy and was leading the mare through the pasture gate. Poppa will take care of her. She trusted her grandfather implicitly. He was an animal lover, if not specifically a horseman.

“Do you need any help getting changed?” Betsy led Ellen into her room. Ellen sat down on the bed and began to toe off her shoes. Betsy’s lips were pursed with worry, accentuating the lines etched into the skin around them.

Ellen shook her head as she reached down to pull off a sock.

“Ellen, were you knocked out?” Betsy asked. “Do you think you have a concussion? That’s nothing to mess around with. Bernie and I saw a program on football players and concussions.” She paused, exhaling slowly. “Your Poppa and I thought, well, there’s no point in discussing that,” she shook her head dismissively, seeking to drive out the terror of the moment that Ellen had disappeared under the falling tree trunk. “You should get those wet clothes off and rest. I’ll go get your mother.”

Ellen reached out and grabbed her grandmother’s hand, which was warm and callused from working in her garden. “Don’t get Mom. There’s no point. What’s she going to do?”

Betsy sighed again, saying nothing. “How do you feel? Do you think you’re concussed?”

“No, I don’t think so. I mean, I’m not even sure I was knocked out. And if I was, it was only for a second or so. Maybe I just closed my eyes when I saw that tree falling right at me. I really don’t want to go to the hospital.”

Betsy shivered at the memory of that horrible moment. She shook her forefinger at her granddaughter. “Well then, young lady, I’m keeping my eye on you tonight. If I suspect there’s anything wrong with you, I’m taking you to the hospital. Is that clear?”

Ellen nodded and waited until Betsy drew the door closed on her way out. Then, she rose to her feet stiffly, feeling some new aches and pains. In addition to her head, she was sore along her right side, especially at her shoulder and her hip. Must be where I hit the ground. She stripped off her wet clothes and threw them into the laundry basket. She pulled on some dry, light-weight sweats, which felt comfy in the cool air of the air-conditioned house. Maybe I should go see Mom, she considered. She shrugged, then padded down the hallway to her mother’s room. Cautiously, she opened the door to peer inside. As was her mother’s custom, the curtains were drawn and the room, dark. It took Ellen’s eyes a minute to adjust to the absence of natural light. She could make out her mother’s form on the canopy bed. Ellen swallowed her disappointment. Asleep again. Really?

“Mom?” she asked. Then again, “Mom?” But Linda didn’t move, or was she pretending that she couldn’t hear her daughter? Thunder boomed again, but now more distantly. Ellen jumped, but her mother remained corpse still.

“Mom?” She reached out and pushed her mother’s leg. Still, there was no reaction. Ellen shrank back toward the door. It’s the pills they have her on. It’s like Mom’s not here anymore. Ellen shook her head. She’d learned months ago not to rely on her mother for anything. The junk those doctors put Mom on is making her worse now, less herself, not better. Despairing and resigned, Ellen stepped back out of the room, quietly closing the door behind her. She headed to the kitchen and Betsy.

The storm raged on for another half an hour. Ellen and her grandparents were hunkered down in the kitchen when the power went out. The usual late afternoon heat had been driven off by the storm. As a result, the air was cooler than usual. The windows and the front and back doors to the little house were wide open, to let out the heat. As the threesome played gin rummy, they were accompanied by a symphony of croaking frogs.

Ellen propped her chin on her hands, her elbows, on the wooden kitchen table, her gaze travelling about the room. Betsy’s kitchen was cluttered but tidy and decorated in warm earthy browns and burgundies. It was warm and welcoming, just like her grandparents, Ellen acknowledged. Her gaze settled on the clear jar of gummy bears on the kitchen cabinet. Betsy kept it filled, since she knew they were Ellen’s favorite candy. Ellen had shoved her hand into the neck of the gummy bear jar more than once in the days since she and Linda had moved in with her grandparents. Sure, gummy bears are kiddish, but they’re yummy. That’s how things were in this house; safe, comfortable, and thoughtful. There was food in the fridge and in the pantries. I don’t have to try and figure out something to eat because Mom is passed out.

Ellen studied her grandparents. There was a comfortable solidity to them, as opposed to her mother, who was so thin it sometimes seemed as if she was vanishing into mist. Bernie was a substantial man, a little over six feet, and solid with the frame of someone who’d physically worked hard his entire life. His shoulders were stooped and his thinning white hair neatly combed over to the side. His face was tanned from days spent mowing the lawn on his tractor. He had a hooked nose and kind eyes. Betsy was more youthful looking than her husband of forty plus years. She was slender and bronzed from working in her garden. Her jaw length hair was dyed blond and always tidy. She didn’t wear makeup, and she preferred to be barefoot outside. She was still lovely in her seventh decade of life and had large dark eyes that sparkled with humor. Her grandmother reached over with her left hand and scratched Ellen’s back, the way she had since Ellen had been a little girl.

“Want us to deal you in?” Betsy asked, her voice, husky and surprisingly deep.

“No, I’m fine. I’ll wait until the next game.”

“You won’t have to wait long.” Bernie snorted. “This one’ll be over in a few minutes.”

Betsy glanced at her husband, then adjusted her butterfly framed glasses by pressing them up her nose. “I think you’re a little overly confident, Bernie.”

Ellen sighed audibly.

“What’s wrong, Ellen girl?” her grandfather asked. “You feelin’ all right?” He studied her. “Your head bothering you?

“I told you we should have taken her to the doctor, Bernie,” Betsy asserted, brushing a strand of dark hair back from where it clung to Ellen’s sweat dampened forehead. Her action drew everyone’s eyes to the now purple and reddish egg on Ellen’s forehead.

“I’m okay. It’s not my head and I’m fine, honest. It’s just, well, Mom.” Ellen leaned forward, her voice dropping to a whisper. “She doesn’t or won’t pull herself together. I nearly get killed by a tree falling on me and she doesn’t even get out of bed. That’s messed up. It’s been months now. I thought she would get better here, but she’s the same.”

Betsy set down her cards and turned toward her granddaughter, holding her arms open. Ellen allowed herself to be held, though her frame remained stiff and resistant. Neither grandparent responded right away.

“Well, she was resting. The storm didn’t wake her up,” Bernie offered.

“Resting?” Ellen raised a dubious eyebrow. “Who rests all day?”

“She doesn’t know what happened to you yet,” Betsy demurred.

“Of course, she doesn’t, because she’s taken her ‘medicine,’ a lot of good it’s doing her. Besides, it’s not like she would even care.”

“Of course, she cares about you. Your mother loves you,” Betsy stated.

“Really? It’s not like she shows it,” Ellen muttered in a softer voice. “All she does is sleep and go to PT. Some days, she doesn’t even talk to me. That’s how it was in Annapolis. Now that we’re here, she has you two enabling her. That’s what it’s called when you do everything for her. That’s what the counselor told me.”

Bernie lowered his head and gazed down at his opened palms. “Your mother lost so much in the accident. She lost her livelihood and her identity.”

“Give her time,” Betsy suggested.

“Well, now she’s losing her daughter,” Ellen snapped back.

“That’s not fair,” Bernie broke in. “She had a brain injury. These things take time to heal.”

“Bernie, Ellen deserves to be spoken to as an adult. She’s been dealing with this as an adult for more than a year now.” Betsy gave her husband the “eye.” “We should tell her.”

“Tell me what? That Mom’s hooked on painkillers,” Ellen stated baldly. “She takes jars of stuff. She’s addicted.”

“You knew?” Bernie was surprised.

“How could I not?”

“Ellen, Linda is embarrassed, ashamed. You know she was in pain after the accident. The doctors put her on painkillers, and she is having a tough time getting off them. She came back here this summer so that she could get some help. She knew that she couldn’t get clean and take care of you all alone,” Betsy explained. “At least she recognized the problem. She’s working with folks who are trying to get her off all that stuff.”

“They should never have put your mother on it,” Bernie offered. “And maybe you’re right about us doing too much for her since you two moved in.”

“Until now, I’ve been the one taking care of her,” Ellen replied, pushing a hand through her still damp hair. Her fingers met resistance in the tangles, but she forced them through. Her scalp ached from the tug on the swollen egg.

“We know,” Bernie agreed. “We wanted you to be able to be a normal teenager again. We should have been more honest with you.”

Feeling pain rise in her throat, Ellen inhaled shakily and stared at the wall opposite her, at the chicken border that separated the brown wall below from the burgundy above. She struggled to maintain her composure. Again, she felt her grandmother’s hand on her back. That made the tears come. Ellen turned toward Betsy, who put her arms around her. She buried herself in the familiar scent of her grandmother, a mixture of freshly mown grass, sunshine, a little body musk, and lingering traces of her favorite Joy perfume that she dabbed on in the morning. Ellen cried sloppily and achingly, expressing her pain at missing her mother, at the loss of their lives as they’d been. Her grandmother rocked her back and forth as if she were still a little girl.

Finally, when she had calmed down, her face, hot and wet with tears, she took the yellow handkerchief her grandfather held out to her.

“Is that your handkerchief, Bernie?” Betsy asked, scowling with disapproval.

“I always carry two,” Bernie replied. “That one’s clean. I always carry two in case someone else needs one. You know that, Betsy.”

Ellen took the handkerchief and wiped away her tears. Then she blew her nose.

“Ellen,” Betsy began, “You can’t do anything about your mother’s situation. That’s up to her. Now, about you, young lady. Ellen, that horse would have been fine out there even in the thunderstorm. You weren’t using the sense you were born with, running around after her out there.” Betsy’s gaze, steady and unrelenting on her granddaughter.

“Tandy was scared.” Ellen insisted. Her chin firming. “She needed help. I had to get her in,” she muttered. “What if she’d been hit by lightning or a tree had fallen on her the way it almost did on me? I’m going to take care of her,” Ellen insisted. “The way my mom should have taken care of me but didn’t.” Once the words were out there, Ellen cringed, wanting to take them back even though they were what she felt.

“We’re here to help you,” Betsy replied. “You need to stop feeling sorry for yourself, young lady. I know you have been through a lot, but you aren’t alone now.”

Ellen couldn’t stop the words that poured out of her. “My life sucks,” she began. “Yeah, Mom got hurt. She can’t jump anymore. That totally sucks, but what about me? This whole thing sucked for me, too. I don’t want to be here in the middle of the boonies shoveling horse manure every day. Seriously, I hate being here and I hate my life.” Ellen stood abruptly up. Catching the look that passed between her grandparents, she felt terrible. They were trying to be nice to her, and she had just made a bad situation that much worse.

She left the kitchen, hurrying down the short hallway and into her bedroom. Slamming the door shut, she flopped down on the bed, then reconsidered and locked the door. Sure, they could get in if they wanted to, but the locked door would at least communicate that she wanted to be alone.

Feeling miserable, disgusted with how mean she had been, she lay back down on the bed. Her bedroom was sticky and with no air movement. The power was still off. Her wide-open eyes stared at the white ceiling, tears sliding down her cheeks. Her heart pounded, and she felt hot and sick and sad. Why did I have to be such a brat? I hurt Nanna and Poppa. Ellen couldn’t help but reflect that this time she’d been the one to inflict the damage.